The 100-Year Mission To Create

The National Museum Of African American History And Culture

By Robert L. Wilkins

Timeline: The Facts

A Comprehensive Timeline of Key Events in the Mission to Create

the National Museum of African-American History and Culture

I was only vaguely aware of past efforts toward some form of memorial or museum that would honor the rich history and culture of African-Americans. So I began to research those efforts—at first, at least, in my spare time. The research uncovered an on-again-off-again, one-step-forward-two-steps-back record of an initiative that since at least 1916 had engaged some of our most prominent citizens and that nevertheless had been persistently beset and/or ignored. To my mind, this story of what I privately dubbed the “forgotten museum” acutely mirrored the African American experience as a whole, and as its rollercoaster history increasingly consumed my attention, I in due course committed myself to do all I could to make the museum a reality and to see it over the finish line.” ~Robert L. Wilkins

1865 – Washington, DC shuts down for the two-day victory parade of Union troops known as the Grand Review of the Armies. No Black regiments are invited, however, despite the fact that roughly ten percent of Union Army was Black and nearly 40,000 Black soldiers died over the course of the Civil War. An idea of honoring their contributions takes root.

1909 – The NAACP forms.

1915 – The Grand Army of the Republic stages a re-enactment of the original Grand Review. Black leaders form a Committee of Colored Citizens to make sure that Black veterans are properly feted. They decide that Black veterans deserve a permanent memorial in the national’s capital to honor their service. The decision is made that the quest for honor should take physical shape.

1916 – Ferdinand Desoto Lee, a Howard University-trained lawyer and an organizational dynamo, gives form to the Committee of Colored Citizens’ quest by founding the National Memorial Association, with an original mission to build a “permanent memorial to colored soldiers and sailors.”

1916 – Missouri Republican Leonida Dyer introduced HR 18721, the first of many bills inspired by the National Memorial Association to create a monument or memorial dedicated to Black soldiers and sailors. The bill proposed for Congress to appropriate $10,000 up front to defray the cost of planning, designing, and constructing a memorial that would cost no more than $100,000. The bill also proposed forming the National Memorial Commission to supervise the effort. The commission was to be racially integrated.

1917 – The United States’ participation in World War I begins.

1919 – The push for a memorial becomes linked to advocacy supporting the Negro troops returning from the war, the fight against Jim Crow racial segregation, and anti-lynching legislation.

1920 – The National Memorial Association expands the scope of the project beyond the proposed construction of a towering shaft or statue to that of a “memorial building,” a place to recognize the Negro as a fellow human being who has contributed greatly to the nation. The building would not only commemorate Negro soldiers and sailors, but also Negro achievement in business, education, politics, the arts and every other aspect of American life.

1929 – On March 4, his last day in office, President Calvin Coolidge signed Public Resolution No. 107, authorizing a “National Memorial Commission” to construct a memorial building for public meetings, events, and exhibitions as “a tribute to the Negro’s contributions to the achievements of America.” The law conditioned the awarding of public seed money on first raising $500,000 privately.

1929 – A monumental stock market crash in October triggers the Great Depression, seriously impeding fundraising, halting efforts for the memorial building.

1929 – Given the need for funding, the National Memorial Commission asks President Herbert Hoover for $1.5 million owed to African Americans in unclaimed pay to Black Civil War soldiers and in unpaid reimbursements to depositors in the defunct Freedman’s Bank. Hoover says no.

1933 – President Franklin Delano Roosevelt abolishes the commission and transfers its duties to the Interior Department, where it drops to the bottom of the to-list list.

1933 – Ferdinand Lee dies and with that the heart and soul are ripped out of the National Memorial Building idea, which can get no further traction anywhere.

1939 – World War II begins.

1940’s-1960’s – The demand for equal treatment by Black veterans returning from service in World War II inspires action and leads to the Civil Rights Movement.

1965 – Democratic Congressman James Scheuer of New York introduces a bill to create a “Negro History Museum Commission,” appointed by the President, to study the advisability of establishing such a museum. Congress failed to act on this bill, or on several other nearly identical bills to establish a Negro History Museum Commission.

1968 – Following a series of bloody riots across the nation in 1965, 1966 and 1967, President Johnson creates The National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, otherwise known as the Kerner Commission. The Kerner Commission concludes “our nation is moving toward two societies, one black, one white—separate and unequal,” a verdict that appeared on the front page of newspapers all over the country. The Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. called the Kerner Report “a physician’s warning of approaching death [of the nation,] with a prescription for life.”

1968 – Senator Hugh Scott, a Republican from Pennsylvania, introduces a bill that is nearly identical Congressman Scheuer’s bill and, together with the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History, organize a one-day conference on Capitol Hill to publicize and build support for Negro History Commission.

1968 – April 4, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. is assassinated. Riots break out in over 100 cities across America in the ensuing days and weeks.

1968 – Days after King’s assassination, Congressman Clarence Brown announces legislation to create a national museum and repository of Black history and culture in his home district of Wilberforce, Ohio. Brown believes the riots and unrest that follow King’s death “attest to the idea that our nation needs the reconciliation between the races which can be fostered by the museum I have proposed.” Wilberforce was founded in the 1830s by manumitted Black people and had been a center of the abolitionist movement and a station on the Underground Railroad.

1968-1976 – None of the bills introduced from 1968–1976 to create the Wilberforce Museum passed. A National Park Service study later concluded that Wilberforce was an appropriate location for a major historic site, but not for a national museum, and that the Smithsonian Institution should run any such museum if it were ever created. The Smithsonian is not interested in creating a separate entity.

1980 – The National Afro-American History and Culture Commission is established to develop “a definitive plan for the National Center for the Study [of] Afro-American History and Culture” in Wilberforce. The Commission is not given any funding until five years later, and by then, federal support for the Wilberforce museum has withered.

1986 – Democratic Congressman Mickey Leland of Texas shepherds passage of a non-binding Joint resolution to “encourage and support” a non-profit organization in the establishment of a structure to commemorate African American history and culture on National Park Service lands in Washington, D.C.

1988 – The 50,000–square foot National Afro-American Museum and Cultural Center opens in Wilberforce without any official Congressional designation as a “national museum.”

1988-1989 – Congressman Leland and Democratic Congressman John Lewis of Georgia introduce bills to found a National African American Museum in Washington, DC, that would be part of the Smithsonian Institution. The Smithsonian debates internally whether to support this effort. Leland dies in a tragic plane crash while overseeing humanitarian projects in Africa.

1989 – The Smithsonian hires Claudine Brown to head its Center for African American History and to lead an “African American Institutional Study.” This study recommends that the Smithsonian create a National African American Museum, and the Smithsonian accepts the recommendation.

1991-1994 – Congressman Lewis leads efforts to pass legislation creating a National African American Museum. A bill passes the Senate but not the House in 1992; a later bill passes the House but not the Senate in 1994. Congressional opposition leads the Smithsonian to soften its support for creating this new museum.

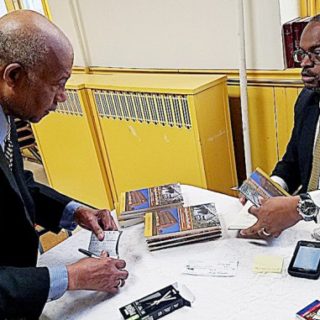

1996-2001 – Robert Wilkins forms a non-profit organization and begins to work with Congressman Lewis and others to push for the creation of a national museum dedicated to African American history and culture.

2001 – A bipartisan coalition of Lewis, Republican Congressman J.C. Watts of Oklahoma, Republican Senator Sam Brownback of Kansas, and Democratic Senator Max Cleland of Georgia lead the efforts to pass a bill to create the National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) within the Smithsonian. With the support of President George W. Bush, the group is not able to get a bill passed to authorize the creation of the museum, but as a compromise, they obtain passage of Public Law 107-106, forming a Presidential Commission to develop an implementation plan for the NMAAHC. Following Lewis’ recommendation, Wilkins is appointed to serve on the Presidential Commission.

2002-2003 – The Presidential Commission meets to study the issues and develop a plan. Dr. Robert L. Wright chairs the Commission, and Claudine Brown serves as vice-chair. Wilkins chairs the subcommittee studying where the museum should be located. The Presidential Commission unanimously recommends that Congress establish the NMAAHC within the Smithsonian in a newly constructed building on the National Mall.

2003 – With Lewis, Watts and Brownback leading the efforts, Congress passes, and President Bush signs into law, Public Law 108-184, formally authorizing the creation of the National Museum of African American History and Culture within the Smithsonian. Congress cannot agree on the location for the museum, so they direct the Smithsonian Board of Regents to study the issue further and select one of the sites recommended by the Presidential Commission.

2006 – The Smithsonian Board of Regents selects a top site recommended by the Presidential Commission for the NMAAHC, on the National Mall and across the street from the Washington Monument.

2006-2016 – Under the leadership of Founding Director Lonnie Bunch and the NMAAHC Advisory Council, co-chaired by Richard Parsons and Linda Johnson-Rice, the $540 million museum building is designed and built, 37,000 objects are added to its collections, and the exhibits are planned. The iconic structure was designed by the team of David Adjaye, Phil Freelon, and Max Bond, the first architects of African descent to design a building on the National Mall.

2016 – On September 24, 100 years after the movement to build this museum began, Barack Obama, the nation’s first African American President, will cut the ribbon to open its doors.

- Credit: Smithsonian Institution Archives