The 100-Year Mission To Create

The National Museum Of African American History And Culture

By Robert L. Wilkins

Magnificent, awful, profound: The stories the new African American museum will tell

By Robert L. Wilkins

September 16

Robert L. Wilkins, a judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit, served on the presidential commission created by Congress to plan the National Museum of African American History and Culture. His book on the creation of the museum, “Long Road to Hard Truth,” was released this month.

Lewis Fraction never imagined that his death would help inspire work toward a museum on the Mall.

“Brother” Fraction and I were mentors in a church youth program when he died 20 years ago, just shy of his 60th birthday, leaving behind a wife and four grown children. While at his home to comfort his family and remember his life, I was struck by the stories told by the elders gathered there.

Stories about the myriad joys of youth — the courtship rituals, old dance steps, swooning over Sam Cooke. Stories about all-black, one-room, ramshackle schoolhouses and the nurturing but stern teachers who presided over them. Some described never seeing a whole piece of chalk or a new textbook — just broken bits and beaten-up books handed down from white schools. There were stories about countless indignities, major and minor, and the psychological wounds they inflicted.

Magnificent stories. Awful stories. Profound stories.

As we drove home that evening, I asked my wife, “Why don’t we have a museum to tell all of those stories?”

This question came with a lot of background. I had spent six years on the front lines of the criminal-justice system as a public defender and seen so much tragedy. When I started on the job, the nation was still in the middle of the crack epidemic and the District was known as the “Murder Capital of the Nation.” I had seen too many gunshot wounds, autopsy reports and bloody crime-scene photos. I had visited far too many victims in hospital beds, clients in jail cells, family members in dingy apartments and witnesses on dangerous street corners. One day I was looking for a witness in the middle of the afternoon when a dilapidated station wagon drove slowly down the street with four or five guys inside. The front passenger was holding an AK-47 rifle pointed upward and at the ready. Fortunately, the car drove past without incident.

Back then, folks called those “war wagons.” I was growing weary of the war.

I was also weary of feeling as if I were always on defense. I knew what it meant to be treated differently as a black man. In May 1992, while returning home from my grandfather’s funeral in Chicago, three family members and I were detained by Maryland State Police so they could carry out a search by a drug-sniffing dog.

It didn’t matter that we refused to sign a consent-to-search form, or that we explained that we were returning from a funeral, or that I told the officer the name and date of the Supreme Court case that his actions violated. As we learned after filing a lawsuit, the only thing that mattered was that we fit a written directive given to the troopers, instructing them to target blacks in rental cars traveling along that stretch of highway.

The settlement of our lawsuit in 1995 required Maryland State Police to document their search practices, including the race of those searched and information on what, if anything, was found. The resulting data revealed an astonishing disparity. The reports showed that the number of black people found with drugs was four times as high as the number of whites found with drugs. But here was the remarkable part: Four times as many blacks were searched in the first place.

As seen in OPINIONS, The Washington Post.

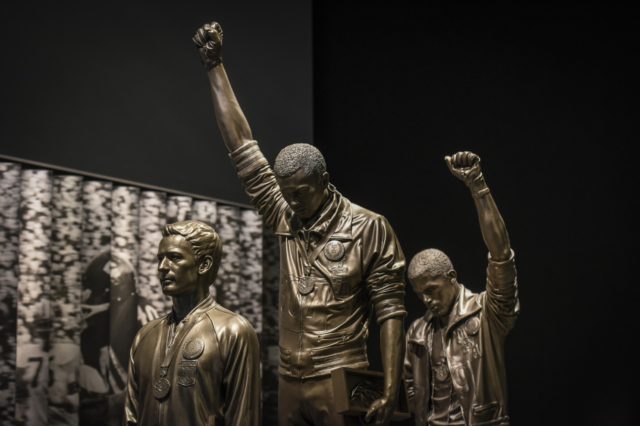

Photo credit: A statue depicting track and field athletes Tommie Smith, center, and John Carlos, right, at the new National Museum of African American History and Culture, which opens Sept. 24. (Jahi Chikwendiu/The Washington Post)

Posted in News & Events on September, 2016